commentary

HBO Max’s hit drama offers a vision of care and connection amid expanding national trauma

Published

Noah Wyle in “The Pitt” (Warrick Page/HBO Max)

From the moment “The Pitt” introduces Noah Wyle’s Dr. Michael “Robby” Robinavitch to his presumably temporary replacement, Dr. Baran Al-Hashimi (Sepideh Moafi), we can see that a shift already guaranteed to be tough is going to be even harder to gut out than he thought.

Al-Hashimi’s competence is not in question, to be clear. She immediately comes off as a magisterial diagnostician and adept leader with bold plans to modernize the Pittsburgh Trauma Medical Hospital’s emergency care experience.

But Robby knows that next to nothing at The Pitt goes by the numbers. The trauma center is overburdened and under-resourced, forcing Robby and his fellow attending physicians to encourage their residents and interns to think creatively without losing empathy for their patients. They get all kinds, from well-to-do couples toting their toy pooches in the same designer bag as their medications, to criminally neglected unhoused people.

Wyle and his co-star Katherine LaNasa, along with the show itself, earned their Emmys the hard way – which is to say, they took a conceit that doubting viewers believe has been done to death and made it feel edgy and acutely human.

Before Robby and Al-Hashimi engage in any real ideological tussles, though, she commits the cardinal sin of suggesting they change the trauma center’s nickname to something else.

“I think it’s just kind of endearing and pretty damn accurate,” Robby demurs.

“I would argue the opposite,” says Al-Hashimi. “I think subconsciously it affects those who work here. It also lowers expectations, which in turn lowers patient satisfaction.”

(Warrick Page/HBO Max) Sepideh Moafi, Taylor Dearden, Katherine LaNasa, Gerran Howell and Supriya Ganesh in “The Pitt”

Creator and showrunner R. Scott Gemmill and his writers wager that we’ll side with Robby in this argument, which is a credit to Wyle’s soul-baring performance and the ensemble’s extraordinarily cohesive chemistry. Wyle and his co-star Katherine LaNasa, along with the show itself, earned their Emmys the hard way – which is to say, they took a conceit that doubting viewers believe has been done to death and made it feel edgy and acutely human.

Skeptics sat down with the first season assuming that Wyle, Gemmill and their fellow executive producer John Wells were trying to recapture their “ER” glory days, only to plunge into an hour-by-hour, heart-forward adrenaline rush more akin to “24,” minus the demand that the audience ignore the realities of crosstown gridlock in Los Angeles.

Every crisis requiring defusing in “The Pitt” rolls right into the team’s midst. The trick is recognizing which ones are visible.

Wells is most famous for guiding “The West Wing” through its post-Aaron Sorkin phase, as well as delivering “Third Watch,” which may be this show’s most thematically similar predecessor. But think about it: As is the case with Jack Bauer, every day we spend with Robby and his team is one of the worst of his year, if not his life.

This second shift that we’re shadowing lands 10 months after Robby and his now-seasoned residents, Trinity Santos (Isa Briones) and Mel King (Taylor Dearden), along with medical students Dennis Whitaker (Gerran Howell) and Victoria Javadi (Shabana Azeez), christened their relationship by making it through a mass shooting event with few fatalities.

It’s also Robby’s final day of work before embarking on a three-month motorcycle road trip set to take him from Pittsburgh to the Canadian badlands. Those who think they understand him doubt he has the will to make the journey. Others can’t quite believe their department’s chair would take such a risk. (This isn’t mentioned in the show, but some medical professionals refer to motorcycles as “donor cycles” for the grimmest reasons you might expect.)

One more thing: It’s the Fourth of July. That means mishaps with illegal fireworks, drunken accidents and a steady trickle of pain, whether physical or psychic. When Robby warns his charges, “There will be blood!” he’s not exaggerating.

(Warrick Page/HBO Max) Katherine LaNasa in “The Pitt”

Production-wise, “The Pitt” is the closest that a prestige drama can get to an extreme sport. Balletic camerawork zooms between examination rooms and the nurse’s station to capture snippets of humanity within a rainstorm of incoming injuries, screw-ups and wrenching tragedies, some of which are invisible until a person who seems fine suddenly flatlines.

But that same sense of daring creates a halo of optimism and comfort in these new episodes without downplaying the sharp messaging about the deteriorating health of our social safety nets, as if that were even possible.

The new season doesn’t ease up on its episodic biopsies of bad policy results piling up on the gurneys lining the trauma center’s walls. Early in the premiere, the camera zooms in on blood cascading onto the floor during a procedure.

Not long after that, we’re reminded that emergency room doctors and nurses are caregivers for society’s castoffs – the forgotten elderly, the unhoused, and families barely remaining afloat. Episodes expose racial disparities in healthcare, the effects of our mass deportation policy on families, and the precarious scaffolding healthcare providers must navigate to support rape survivors.

Every day, the folks in The Pitt confront death and chaos. Those same shifts also rain down miracles and blessings. This is directly quoted wisdom from Donnie (Brandon Mendez Homer), a nurse, relating this in passing and in personal terms. But it instantiates the way the story holds its jumble of optimism and disaster in a firm, two-handed grasp: death and chaos on one side, miracles and blessings on the other.

While we have a better idea of what to expect this time around, the nine new episodes provided for review prove Gemmill and his writers haven’t dropped a stitch. Layers of silent tension electrify the air throughout these early hours. Some of that is obvious, like Robby’s collisions with Al-Hashimi related to her insistence on adapting a digital charting system powered by generative AI. Or Santos bristling at her new boss’s insistence on clearing her charting backlog while tending cranky patients.

This extremely human rendering of the healer’s challenge conveys a broader scope of comprehension than any other medical drama.

The rest pulls at the strings of the audience’s latent anxiety, waiting for the other shoe to drop. We wouldn’t be tagging along for this shift if some dam, somewhere, wasn’t destined to break. This being the show’s sophomore season — and this being television, a medium that runs on stakes constantly raising – why stop at one proverbial dam blowing open? Why not two, or three?

If you are wriggling in the gigantic, sticky net of grief that is our national gloom, falling in with “The Pitt” may not seem like the right medicine for this moment.

Fearing that it could worsen our collective mood isn’t unfounded. But what prevents this pile-up from darkening into a doom spiral is The Pitt’s people. Doctors like Mel King, whose neurodivergence manifests as open, radical caring and diagnostic precision, or Whitaker, who was revealed to be unhoused himself at the end of his first season baptism by disaster.

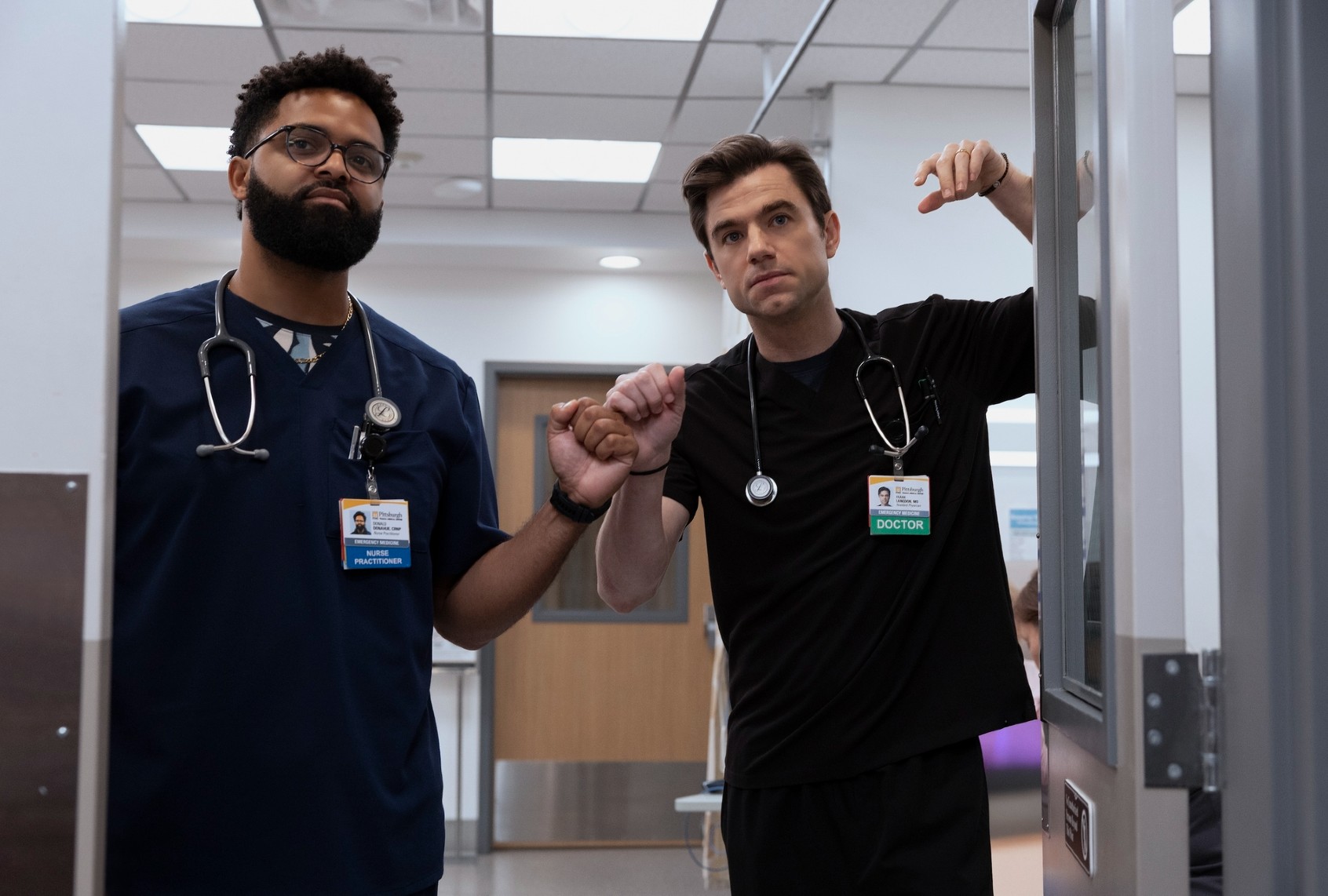

(Warrick Page/HBO Max) Brandon Mendez Homer and Patrick Ball in “The Pitt”

Nurses like LaNasa’s charge nurse, Dana Evans, the place’s heart and mettle, or Princess (Kristin Villanueva) and Perlah (Amielynn Abeller) gossiping in Tagalog. One-time guests like the elderly charmer who flirts with Dr. McKay (Fiona Dourif) to distract himself from an agonizing injury that threatens to slow down his dating life. Endearing heartbreakers like Louie Cloverfield (Ernest Harding, Jr.), an alcoholic who keeps coming back because this is the place where everybody knows his name, not any bar.

“The Pitt” spent its first season suturing our heartstrings to these characters by way of an impressively profound level of character development, rounding out the individual quirks of seemingly minor recurring characters.

This extremely human rendering of the healer’s challenge conveys a broader scope of comprehension than any other medical drama, even if Robby’s struggles to refrain from taking every victory or failure personally fit a prevalent archetype.

The main quibble with this second season is the writers’ heavy reliance on our fondness for the returning cast, which comes at the expense of newcomers like Al-Hashimi or the latest crop of medical students. As the drama’s Virgil, we’re conditioned to accept Robby’s view of the world as just or at least excusable. That automatically predisposes us to distrust the woman charged with holding down the fort, which isn’t quite fair.

If we are collectively experiencing some version of national trauma intentionally inflicted by those intending to lock us in a system of adverse health outcomes and medical debt, then all we can do is look after the people reaching out for help.

Similarly, we’re conditioned to embrace Javadi’s eagerness to impress while softly despising James Ogilvie (Lucas Iverson), a fourth-year hotshot gunning for her slot, or anticipating the day the talented but disaffected third-year medical student Joy Kwon (Irene Choi) moves along. It’s hard to overlook the relative lack of dimension the writers grant these characters, regardless of how often Robby advises against assuming too much about people and their capabilities.

Of course, he doesn’t always swallow his own prescription, especially when it comes to Dr. Langdon (Patrick Ball), whose return to work after rehab takes Robby by surprise. Suddenly, the man who urges his charges to work as a team can’t forgive the coworker he once trusted the most.

Dana releases old slights more easily; there are too many people to save to dismiss a pair of capable hands. This season has her shepherding a new-minted nurse (Laëtitia Hollard) through her first day with a sense of protectiveness even as she tosses the kid into the fray. That Dana refers to her as a lost lamb upon first laying eyes on her underlines this dynamic while reminding us of how she sees herself and why she keeps showing up to bring order to this thankless mess.

Want more from culture than just the latest trend? The Swell highlights art made to last.

Sign up here

That, I think, is the drama’s central lesson, and the reason it feels calming instead of hitting us with endless jolts to the nervous system. Optimists and happy warriors entreat us to lean on each other to get through these grim times, insisting that community is our strength. Even so, you can’t be blamed for not wanting to leave your house, and nobody says that you have to. “The Pitt” ably accommodates the couch-bound walking wounded. “We do what we can to provide the best care to traumatized people in their darkest days,” Dana quietly says later in the season, at a point when ample evidence proves the honesty of that mission statement.

On any given day, that describes millions of us, a nation forced to watch as its leadership celebrates keeping federal employees in trauma and bracing ourselves for the downward impact on our lives and wellness. (About that . . . how affordable are your healthcare premiums these days?)

Never does “The Pitt” allow us to forget that the American dream is the invisible triage victim in this trauma center and the hundreds like it. But it also reminds us that people who care keep those of us shortchanged by its promise limping along.

If we are collectively experiencing some version of national trauma intentionally inflicted by those intending to lock us in a system of adverse health outcomes and medical debt, then all we can do is look after the people reaching out for help. Trauma is a part of life, and without addressing the root causes of it, repeating it is an inevitability.

This time, though, “The Pitt” also counsels recalibrating our concept of what’s important, whether that means reevaluating our focus on our jobs over our families or other choices about how we’re living. “Is this how it works?” a patient in dire condition asks Robby. “You think things are important, like everything’s so important, then you end up here and see?”

“Yes,” Robby grimly answers, “that is how it works.” With that, he continues making his rounds.

New episodes of “The Pitt” stream at 9 p.m. ET Thursdays on HBO Max.